The Risk

The grandmother risked it all by not mentioning the return address. If the letters were misplaced, there was no single chance to get the letters back. Knowing all this, the risk was taken and the letters were sent to the postmaster.

It Worked!

Cramblit’s risk was worth. Boes and her colleagues proceeded with the next step that is giving the letter in the hands of an expert. The search for surviving relatives of the author began. It was more of a personal mission for the research analysts.

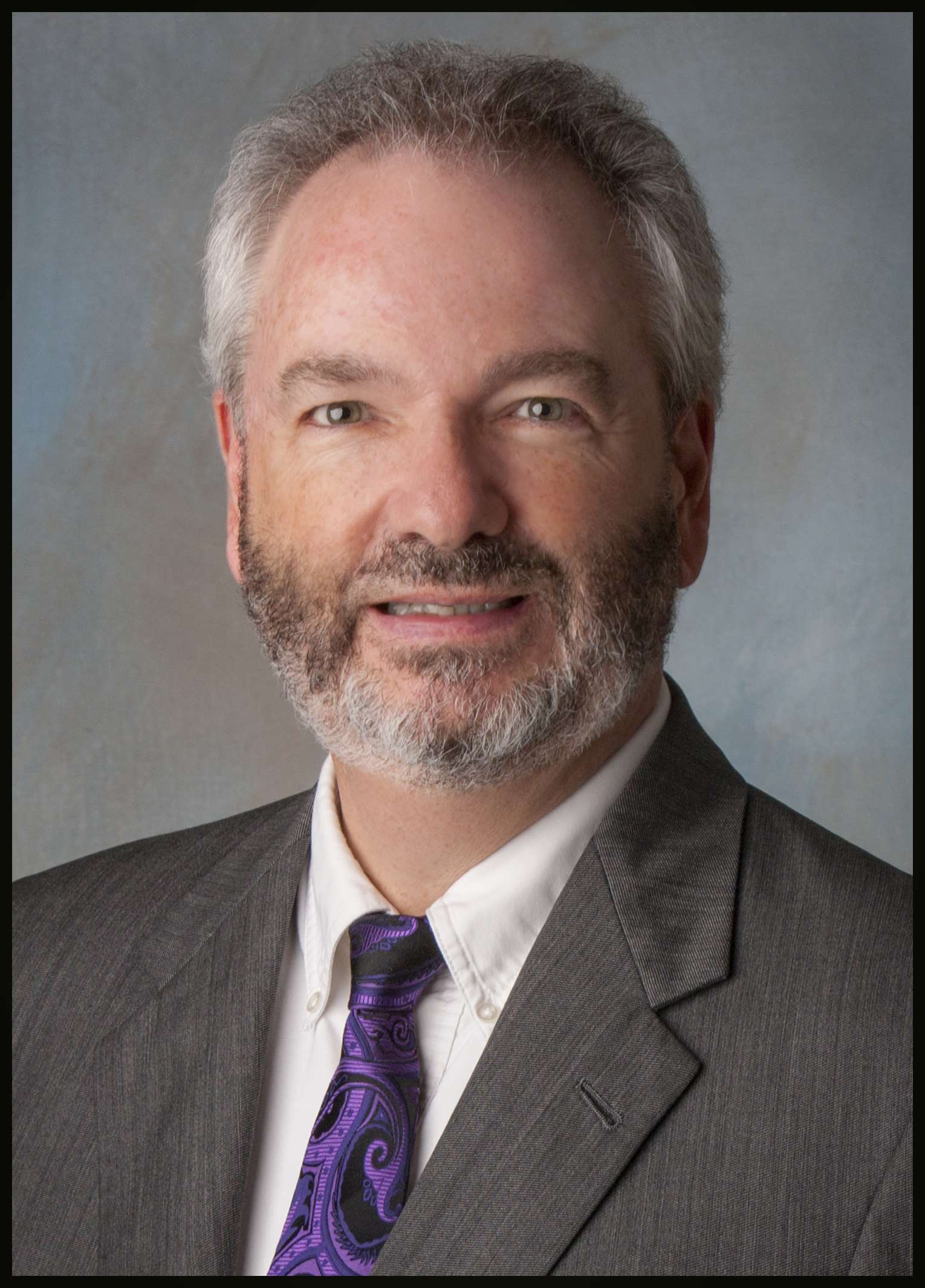

Opinion

Kochersperger while working on the case, told the Smithsonian magazine, “I identified with [Shephard] as a boy off to see the world. I could also identify with his parents since I have five kids of my own.” Being emphatic, he started analyzing the letters and the case took a different direction altogether.

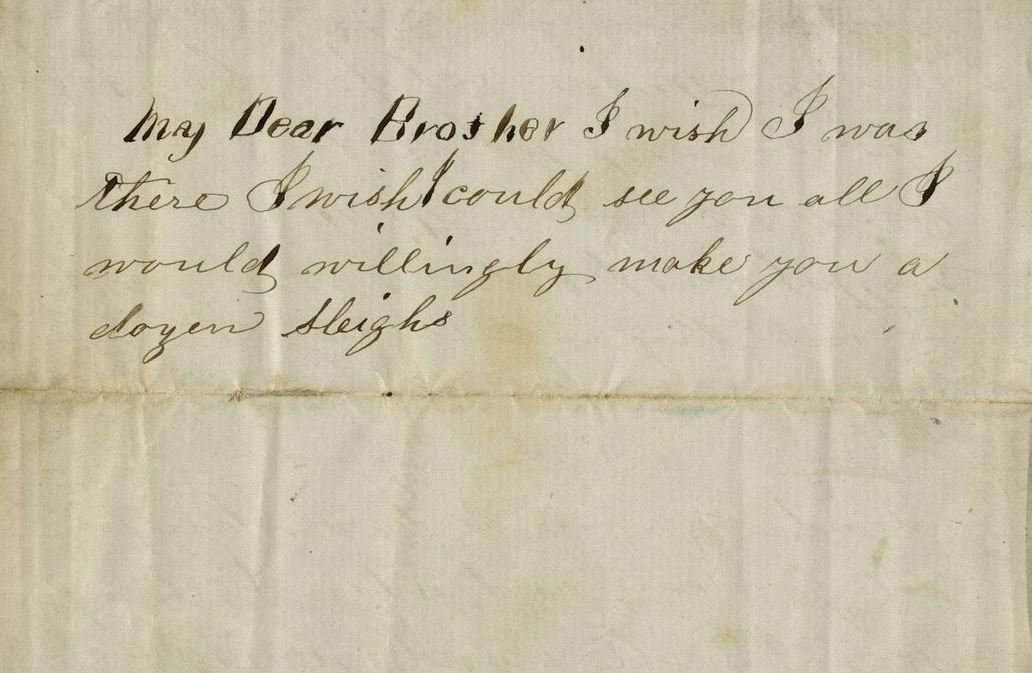

Interesting!

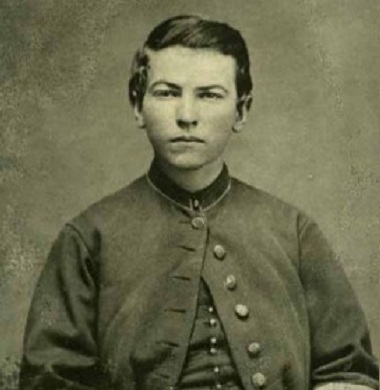

While analyzing the letters more closely, Kochersperger discovered that one of the letters was written to the brother. It appears that only the notes to Albert, Shephard’s brother, was written by the soldier himself. Although the majority of Civil War soldiers were literate, it’s presumable that many preferred to dictate letters to those with faster, more readable handwriting.

In-Depth Study

Kochersperger was to chronologically arrange the incidents described in Shephard’s letters with those recorded in the history books. The researcher went through several sources, such as newspaper archives, census, and military records. But most striking among them was The History Of Livingston County, Michigan by Franklin Ellis which was published in 1880.

Disclosed

From all the studies he went through, he got to discover that Shephard had been born around 1843. He’d also been the eldest of three children born to Sarah and Orrin Shephard. In the 1850s, the family had called Grass Lake, MI, home. But they’d later moved to White River.